“Do you believe in God?” I asked my mother. She was at this point in kidney failure and on hospice at my house. She had weeks to live.

Chem kider, axchigs, kichmu shat hekyatayin paner en, she responded. "I don’t know, my daughter, it is all a bit too much like a fairy tale."

That she would say this, came as no surprise. The woman had avoided any form of organized religion her entire life.

Martun xijn e iren astvats, she’d say. "Your conscience is your God." Simply the most generous person I know, she never wanted anything and did not like gifts. When she’d hear that someone was in need, she’d ask me for money to give to them.

Yes, kezi verch gudam, she’d always say. "I’ll give it back to you." However, she never had any to give back. She grew up with her father, a Protestant preacher, travelling and proselytizing in Bulgaria and there are pictures of him with a group of newly baptized Gypsies. I don’t know for sure that they were Gypsies, but that’s what my brother told me. Maybe it was this childhood or maybe it was the fact that many proper, religious people turned away from her when she needed help, but my mom had a “go it alone” attitude to all things, including religion. She’d often say that after my grandfather and aunt were imprisoned in the USSR after repatriating from Bulgaria to Armenia, everything turned upside down.

Yerpek ches kider ov e lav mart yev ov vad, she’d say. "You never know who is good or bad." You cannot make that judgment because when the time comes, you will be rejected by most, but help will come from those you least expect. I’ve found this to be true.

My father’s faith was never in doubt.

Yes kidem ki dghais bidi noren desnam, he said after my brother’s death. "I know I will see my son again." He’d been an altar boy in Alexandria, Egypt and never outgrew it. After repatriating to Soviet Armenia, he did not go to church. No one did. He did, however, make a point of taking me to be baptized at the age of eleven. After we came to America in 1976, we would often go to St. Garabed on Alexandria Ave in Hollywood. He never asked me to go with him. It was I who asked. On Easter—his name day, we had our ritual. We’d go to church as my mom would stay at home, making chorek. We would sit side by side, he would sing along during Mass and afterwards, we would light candles together. When he went by himself, he always brought mas --

communion-- with him. It was for me, indeed, for all of us. I can’t say that he was taken seriously, because for a long time we all thought of his actions as relics of a past time. We did not see his faith’s relevance to us and to our lives. I know I didn’t. It was ritual, something I shared with my father and loved, but didn’t understand how it related to our lives or the anchor it would become.

It wasn’t until my brother’s illness, that faith became at all important. Both of my parents were dealt the toughest hand that could be dealt to anyone. I watched how their faith, so different and yet so similar, sustained them. My father went to church regularly and would light a candle for my brother and our family. My mom was angry with God and had no patience for any of it, but I believe that she needed for my father to believe the way that he did.

Where did I come into all of this? I don’t think that I believe as solidly as my father but I also know that I cannot do it alone like my mother did. I need the community, the ritual, the language. I need all of it. To be in church, to participate in rituals thousands of years old, to know that each step I take has been taken by so many before me gives me a sense of peace and a continuity that leads directly to my own vulnerability. I wish I believed as simply as my father. Mine is a belief system riddled with doubt—I overthink things, I know. I once asked Fr. Vazken about this. Don’t worry about it, was his response. Connect the other dots, focus on action because that’s the hardest part.

This is very much like the advice given by my grandfather to my aunt. At fifteen, she told him that she was an atheist and didn’t believe in God.

Lav, aghjiks, tun miyayn naye lav mart ullas. Ure inch pes kogin xighj gu badvire. Bayts Astvats ga. Tun naye lav mart ullas. "It’s ok, daughter, try to be a good person and do as your conscience demands, but God does exist. You just be a good person." In fact, when my own father was in the hospital, talking to my son Alek, he stressed the same words--

Dhags, lav mart ullas. "My son, may you be a good person."

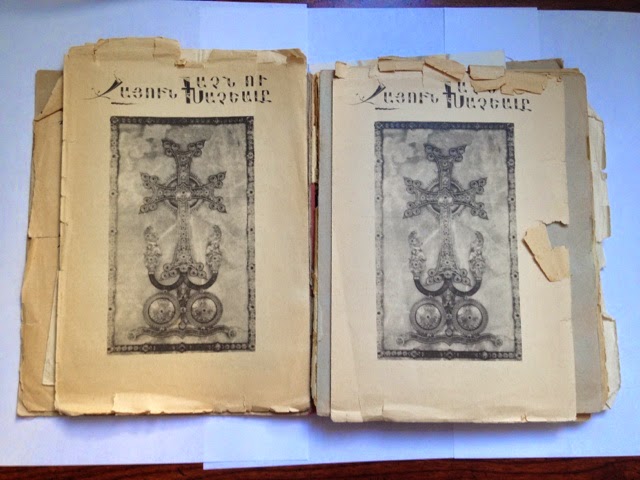

So, I suppose, for me that’s what is truly legitimate. Trying to be a good person, following my conscience and being in a place that provides a connection to my past, to my father’s faith and that has meant finding my home in the Armenian Apostolic church. More specifically, it has meant committing to and being embraced by the community of St. Peter’s—the little church on the corner.

When you go to America send me, please, answers to the following questions.

When you go to America send me, please, answers to the following questions.